The world through the art of Matt Rota

Dossier is very grateful for the time Matt Rota spared us to tell us the background story behind a few of his illustration works. Matt is based in Brooklyn, NYC and while illustrating for the most prestigious publications he also lectures at The School of Visual Arts. The stories behind the illustrations are as powerful as the artwork itself.

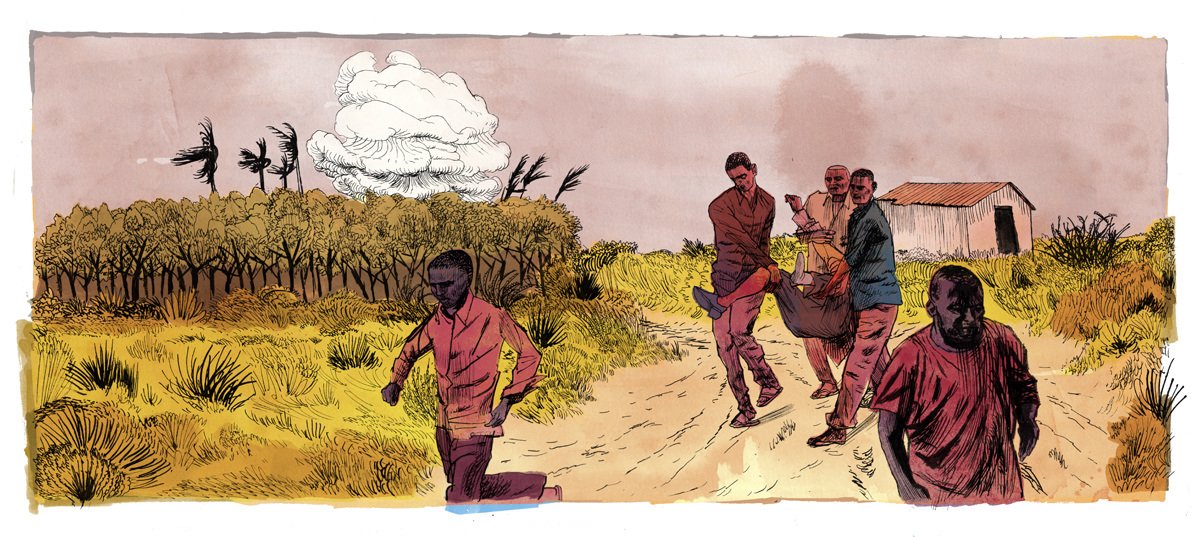

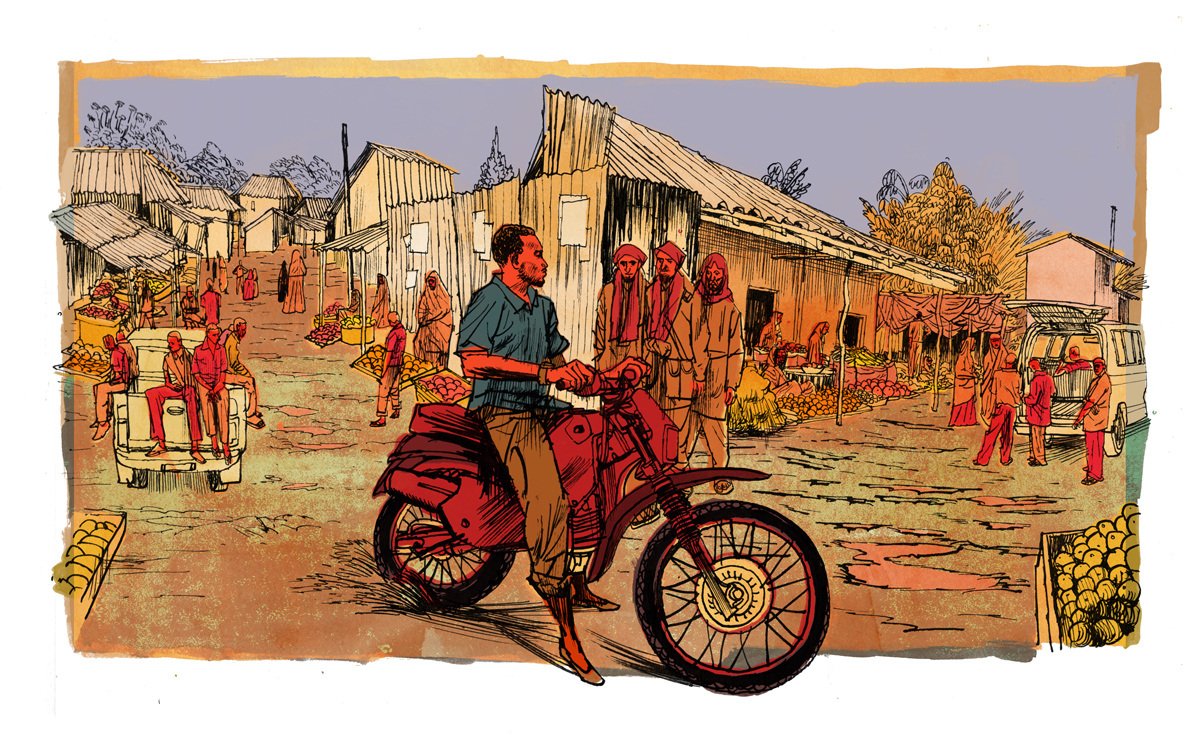

CIA Bombings of Somalia

This was for the publication “In These Times”. It came out under the Trump administration and was about how he gave the CIA free reign to engage Al-Shabaab however they wanted in Somalia, which resulted in the development of covert operations focused on drone bombing. Good intel is historically hard to gather in Somalia, so the attacks were more haphazard and reckless than usual. Typically when the CIA drops bombs it has to take responsibility for it, those records are public and journalists can access them, but in Somalia, the unique situation that Trump authorized for CIA bombings in this case unless a journalist could inquire about a bombing in the exact location at path the exact time, the CIA did not have to disclose any involvement. This article attempted to track particular instances of those bombings as well as the collateral damage. Specifically the destructions of farms and livestock and the effect that had on the population. Many of the farmers are adverse to Al-Shabaab, but because of the covert nature of the attacks by the CIA, have an easier time negotiating with the terrorist group than the CIA, and as their infrastructure ad jobs are being destroyed, they find themselves more at the mercy of the devil they know than the one that bombs them from invisible locations.

I worked on this with a journalist in Mogadishu, we chatted over What’sApp. She would send me cell phone footage of farms bombed by the CIA and transcripts of interviews with farmers. Because of the nature of a project like this, details were important. She would describe specific scenes, and the details had to be well researched. The Somali men had to LOOK like Somali men. In the market scene, for instance, it had to be a specific bike. The Al-Shabaab members had to have specific clothing, scarfs, etc. The market had to look correct, the fruit on cardboard on the ground instead of tables. There was a lot of discussion over those details. Even the smoke cloud from the bombing, this was important because it had to be the sort of bomb that the CIA would drop, not say, from a grenade or other missile, otherwise it would potentially discredit the accusations against the CIA. With a topic like this there is a lot of responsibility for accuracy and representation for the sake of credibility, and In These Times is very meticulous, which I deeply respect, and enjoyed engaging with.

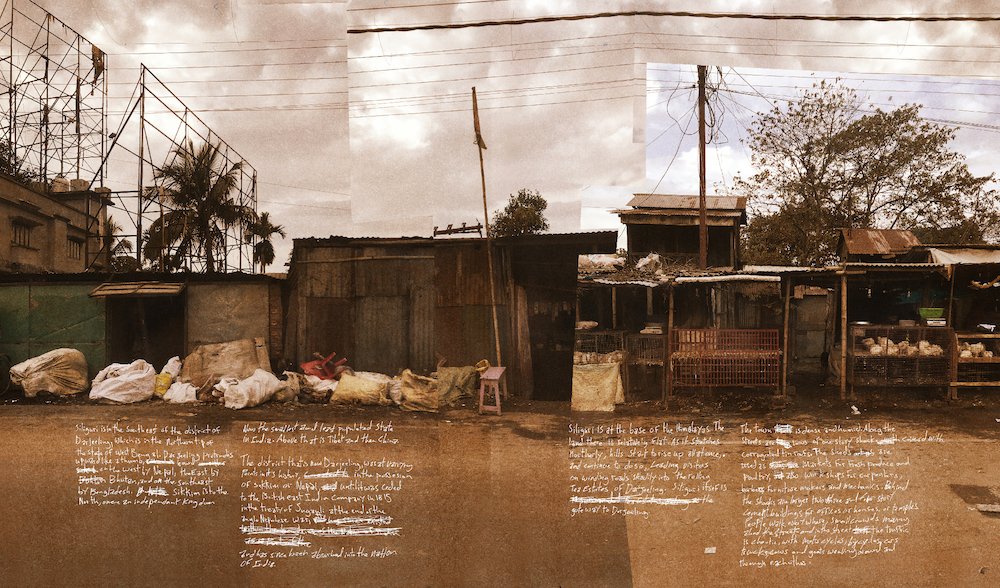

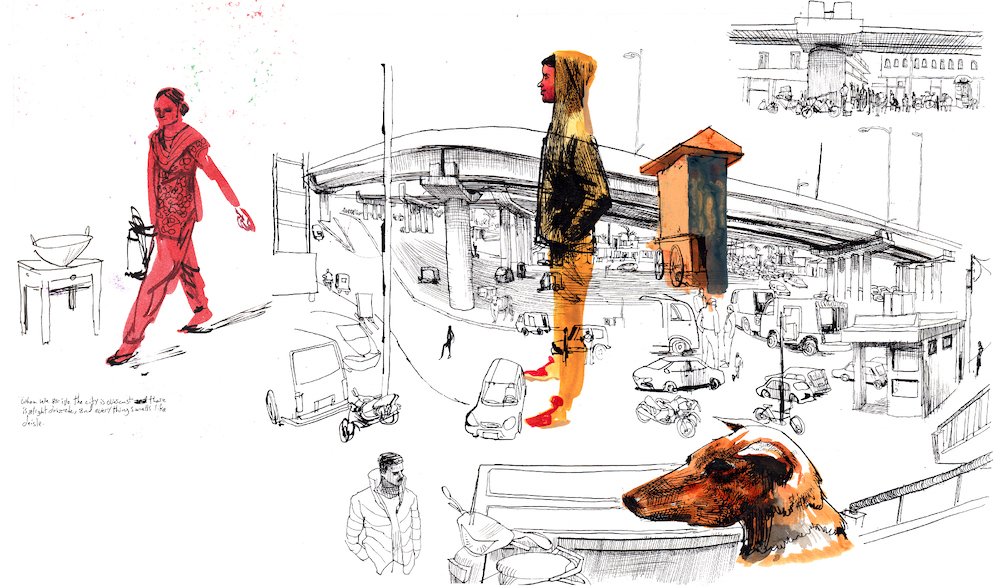

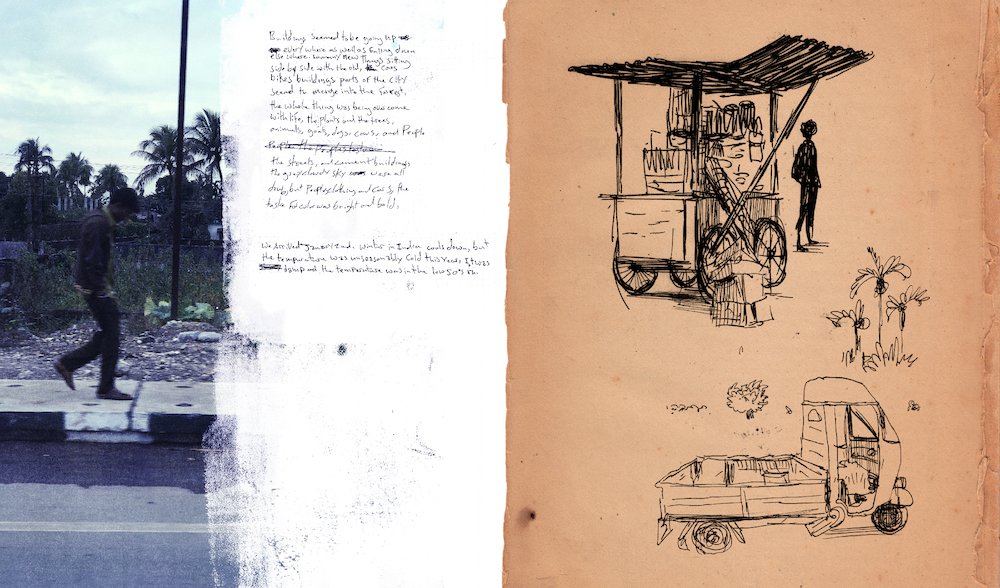

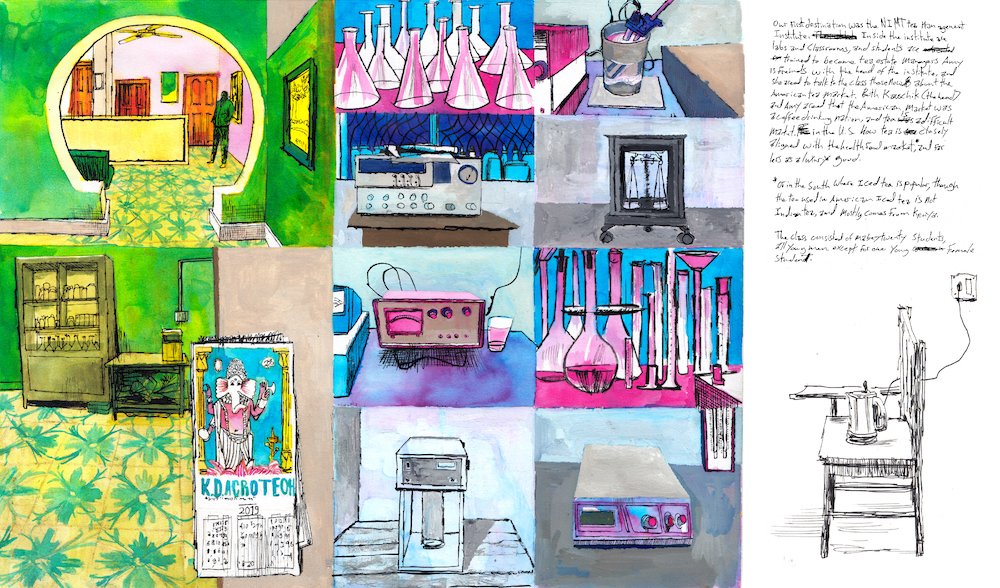

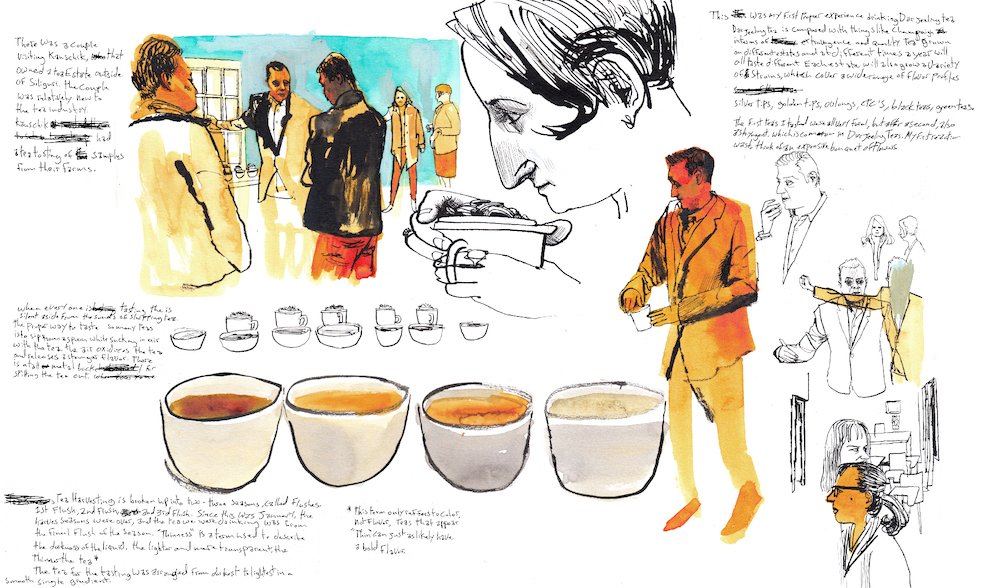

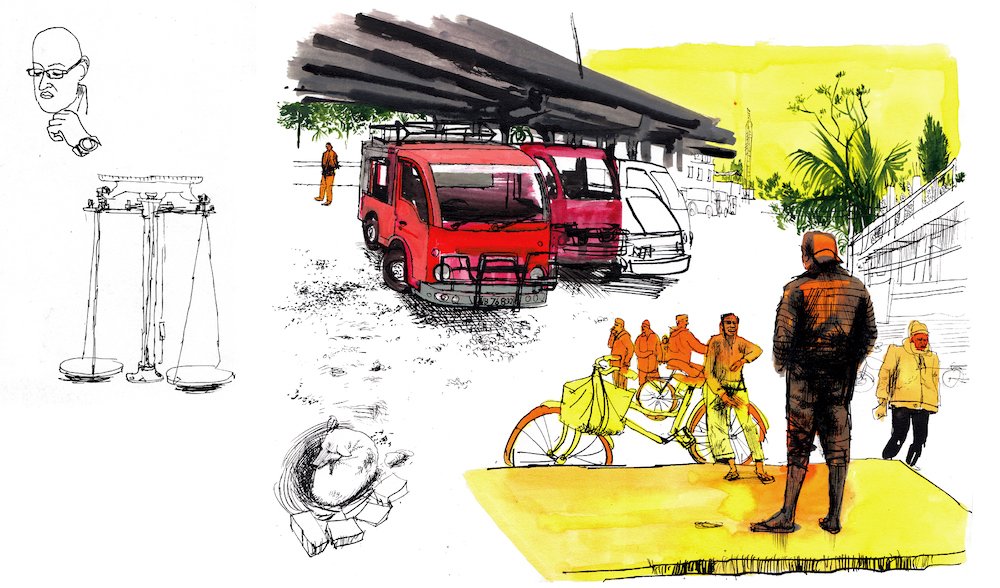

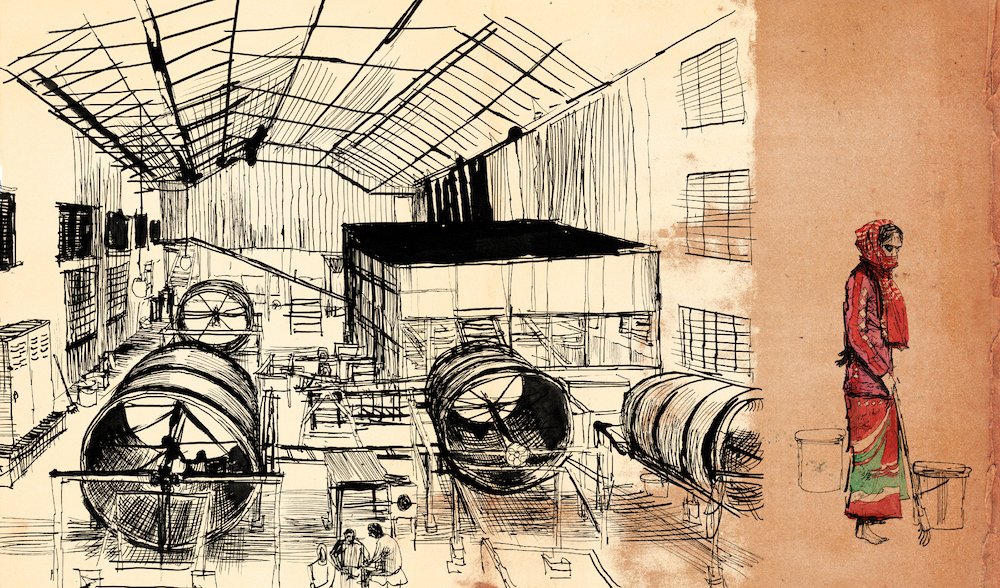

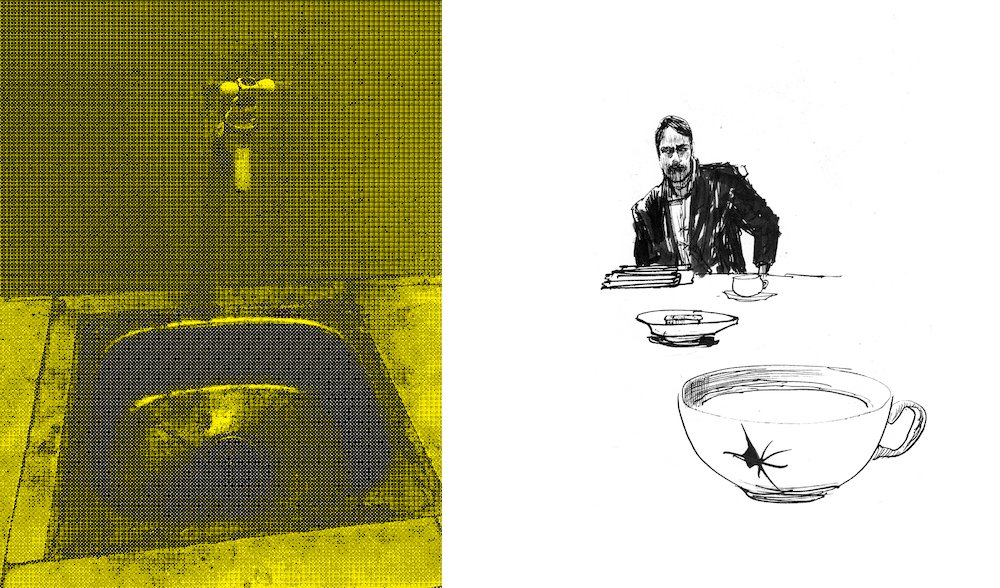

India Tea

This is a personal project. Something I started before the pandemic. As you can probably tell, I’m interested in global politics and history. I like research, and working on projects that give me a better understanding of how the world works and how people in different parts of the world live. I have a friend who works in the tea industry and she invited me to travel to Northern India in January of 2020. I’d never been to India and knew practically nothing about Indian Tea. We spent a month traveling to tea estates in the North of India, Darjeeling, and Assam, learning about tea production and its history. I kept sketchbooks during the trip and have done hundreds of drawings since. I’m putting all of that work together into a travelog that’s in essence a journal of my evolution as a tea lover, and in my understanding of the complex history and legacy, tea has in India as a colonial transplant. The History of tea production in India mirrors the history of agricultural labor in post-colonial nations and can be used as a sort of prism to understand the relationship many of those nations have with global markets in Europe and the United States. Darjeeling Tea is grown in the very dramatic landscape of the lower Himalayas on the border between India and Nepal, in communities built by the British in the 19th century. Tea is not native to the region, or India before the 19th century, but was grown there by former British Military officers from plants stolen from China in an attempt to compete with the Chinese global monopoly on the industry at the time. Many of the farmers that grow tea in Darjeeling and Assam come from populations that were imported by the British in the 19th century from other regions in India for tea cultivation. The tea they grew, and still grow in Darjeeling and Assam is primarily for European markets which is the origin of the distinction between the milky spiced Indian “Chai” and the plain “British Style.” This is still very much a work in progress, something I’m working on with a lot of help from my friend Amy Dubin who I was traveling with, and who is extremely knowledgeable about the business and culture of Indian tea. These are some of the initial spreads I’ve created from my drawings of the farms and factories I toured, the estates that were kind enough to host us, and all of the spaces and people and towns in between. This is something I hope to try and get published once it's done.

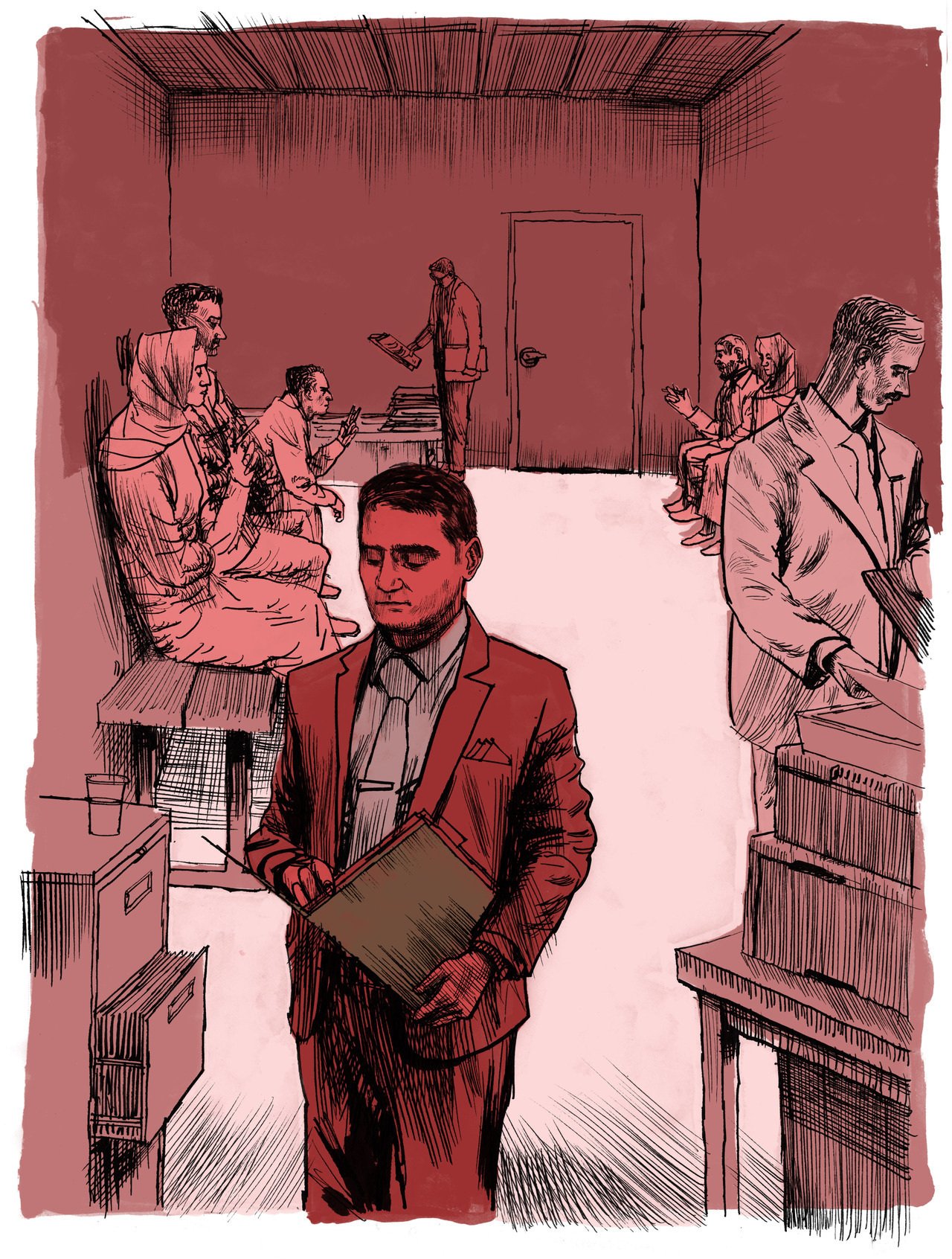

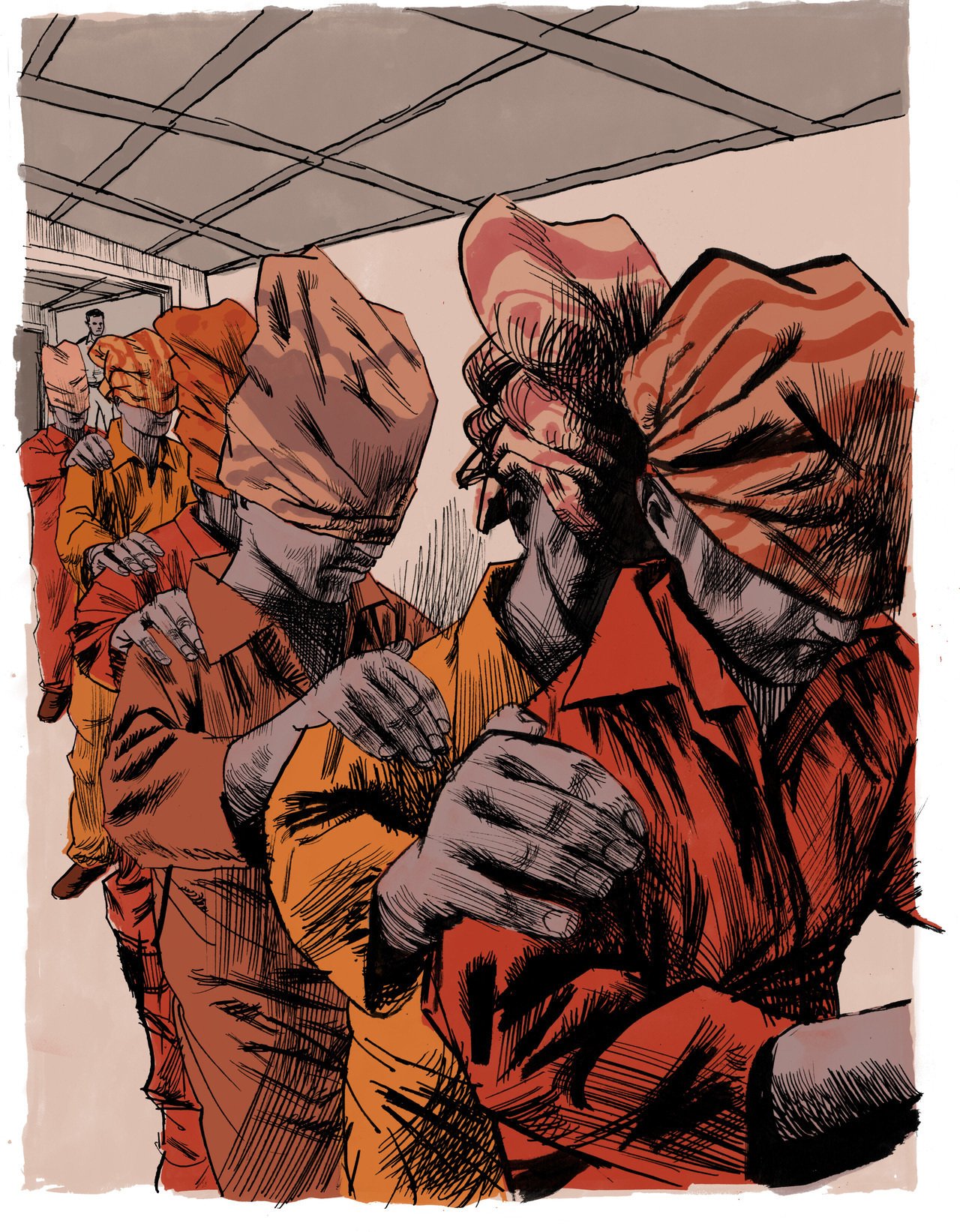

ISIS Trials

These were for “Zeit Magazine”. This was during the Trials in Bagdad after ISIS was driven out of Iraq. There were no photographers allowed in the trials, so I was working with a journalist in Bagdad. He would attend the trials in the daytime and go back to his hotel at night and Facetime me from his unlit hotel room where he was sitting in bed in a bulletproof vest telling me details about the trial and courtroom. In particular, the trials were along religious lines, ISIS being Sunni fundamentalist, so the trials had a deadly religious context. The accused ranged from militants to people forced to drive cars for the Islamic State, and other lesser jobs, often because their family was being held hostage by ISIS. Those facing trials would have their heads wrapped in beach towels so they couldn’t see anything, and were led into the court in a long line, their left hands on the shoulder of the prisoner in front of them (seen in one of the illustrations). These were the sort of details the journalist talked about. I had to take notes and make sketches from them and send him pictures, we’d go back and forth on the details until he was comfortable with them.

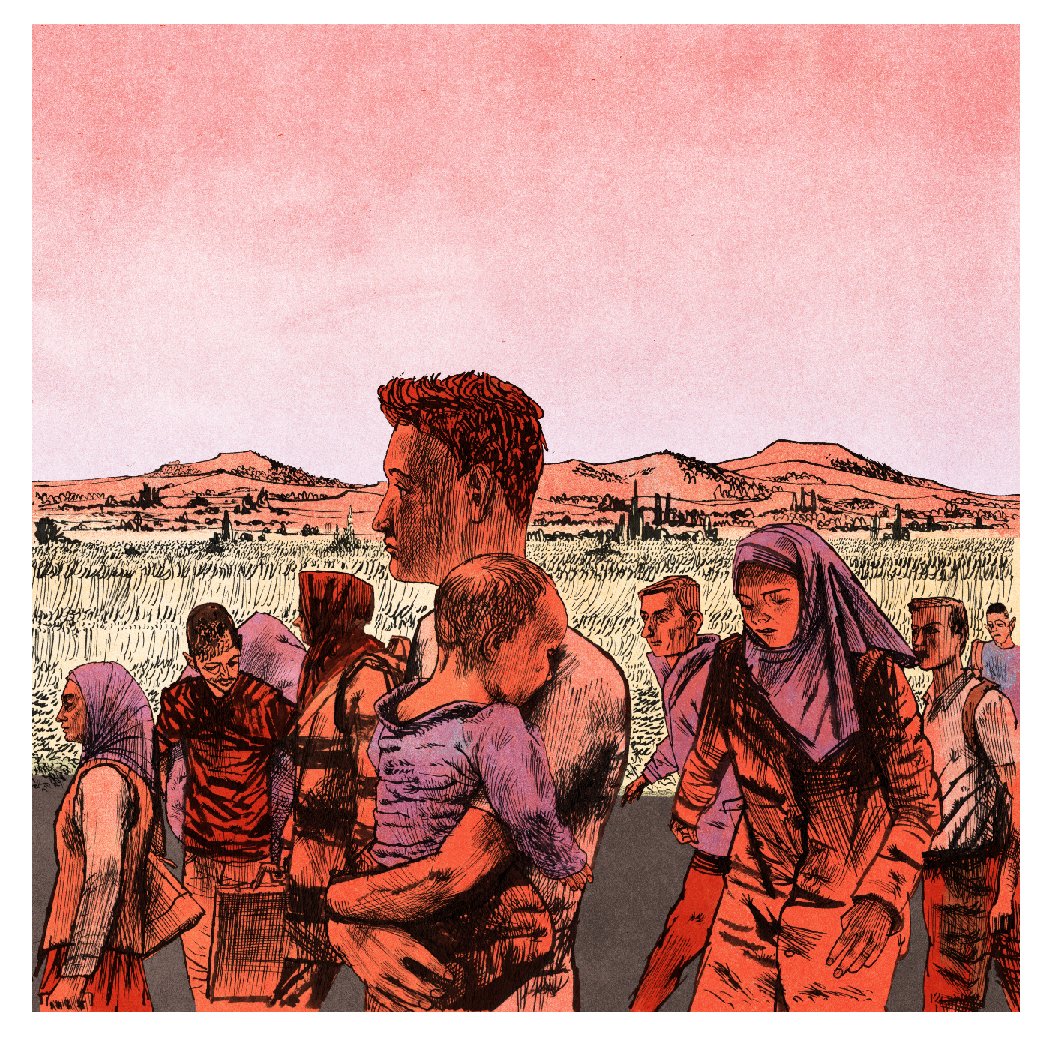

The Lost Generation

This one was for “Foreign Policy”, they ran a podcast earlier this year on the anniversary of the start of the Syrian Revolution. The podcast was about the children that grew up in refugee camps in Lebanon. Their struggle to get an education, and have basic amenities like proper plumbing and heating in the winter. This is another one that dealt a lot with research and accuracy. The work I do is not necessarily realistic, it has a journalistic quality, but also a cerebral, expressionistic distortion to it. I want the people and places to feel real not like concepts, rather like actual specific places, but also there is a risk in being too accurate that the drawings become too technical and cold. I want also for the viewers to feel something, to have an emotional reaction, primarily I want the drawings to create a sense of empathy, but without them feeling sentimental. That's the balance I always try to strike. If the people and places feel real, they are more human, more relatable, and that is essential in a story like this, or anything dealing with war and related traumas. Something too abstract keeps the reality at a distance keeps it vague and kind of “over there” somewhere far away and easy to forget. In cases like this, I want to be sensitive to the people in the story, give them dignity, not use the trauma in the story as the subject in a way that feels exploitative or sensational either. It is essential with art to build human and emotional connections.

ABOUT Matt Rota. A graduate of The Maryland Institute College of Art and the School of Visual Art, Matt is an illustrator, author and instructor. He has spent the past 15 years working with clients in print and online including the New York Times, the New Yorker, Penguin Books, The LA Times, The Washington Post, Foreign Policy, The New Republic, Smithsonian, Variety, Buzzfeed, and many others. His illustrations focus primarily on global politics, criminal justice, social inequality, immigration and poverty. Over the past ten years he has taught illustration at the Maryland Institute College of Art and The School of Visual Arts. Matt has written two books on drawing, has an extensive exhibition career internationally, and is senior curator at artreprenuer.com.

Bookings: https://www.illustrationzone.com/

https://www.instagram.com/illustration.zone/

https://twitter.com/IllustrationZo1

https://www.linkedin.com/in/illustrationzone