Danijel Zezelj- Graphic Art Wizard

Danijel Žeželj’s career began in 1993 with Il Ritmo Del Cuore, published in Italy, with an introduction written by no less than Federico Fellini. He then developed a lasting working relationship with French publisher Mosquito, and with American publisher Vertigo. He has written his own stories, and worked on stories written by Darko Macan (2002, The Sandman Presents: The Corinthian, Captain America), Brian Azzarello (2000, El Diablo, 2006 Loveless), Warren Elis (2006, Desolation Jones), Andy Diggle (2008, Hellblazer), Steve Gerber (1999, Heart Throbs), Chck Austen (2002, Call of duty: The Wagon), Brian Wood (since 2007, DMZ, Northlanders, The Massive, Starve), Scott Snyder (2011, American Vampire), Jean-Pierre Dionnet (2012, Des dieux et des hommes T03), Jason Aaron (2013, Scalped), Aleš Kot (2018, Days of hate).

After your studies of classical painting, sculpting and printing at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb, Croatia, you remained for a time in London, then Italy. Your first published professional work is Le Rythme du Coeur, with an introduction by film director Federico Fellini (1920-1993). How did Fellini happen to write an introduction for a beginning artist?

I published my first short comics in the Italian magazine Il Grifo, and Federico Fellini was associated with the magazine, he was also on the board of directors. Fellini was a big fan of comics, and passionate about drawing and painting, he created numerous sketches for sets and characters for his movies. Il Grifo was one of the best comic magazines in Italy and Europe at the time, publishing work by Hugo Prat, Manara, Liberatore, etc, before it went bankrupt a few years later as all the comics magazines gradually disappeared and audiences turned to books, or graphic novels. Fellini saw the work I sent to Il Grifo editors, and he liked it immediately. So when Editori del Grifo decided to publish my first graphic novel Il ritmo del cuore (which was actually my third graphic novel but the first two have never been published), he was happy to write a few sentences of introduction. I was extremely honored, especially since I grew up on Fellini’s movies and Amarcord is still one of my all-time favorites. Generally, the Italian directors, from Rossellini to Pasolini, to Fellini, together with French new wave, as well as silent movies, were a very important influence on me and my work, just as the cinema in general.

(Above: Vincent Van Gogh)

What can you tell us about your mostly B/W art?

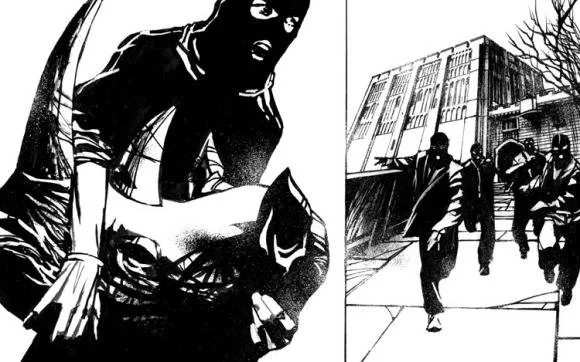

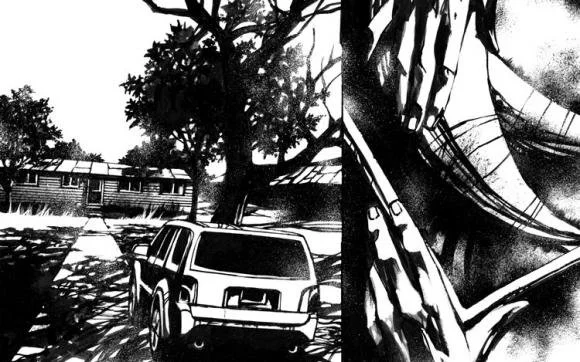

It’s a style based on the contrast of light and shadow. My background is in painting, I studied classical painting at the Academy of Fine Arts, and I was particularly drawn toward baroque painting, especially work by Caravaggio and Velazquez. Baroque painting is based on the relationship between light and shadow, ``chiaroscuro”, that’s how you build forms and shapes. I try to apply to my work the same patterns baroque artists were using in oils, the same principles. When you are looking at things in chiaroscuro, light and shadow, you do not start from white canvas, you start from a middle tone, usually a sepia tone, they often used a raw umber color. You cover the whole surface with raw umber, and then by taking the color out you get the lighter parts, and by adding more umber you get the dark. You are thinking differently; you are thinking in terms of shadow and light. You do not see the line: the line is excluded. So I applied this same idea, sharpening the contrast and reducing it to only black and white.

Who are the painters you looked at most closely?

I looked a lot at Caravaggio. I think, more than anyone else, he really mastered this approach in which the subject is always emerging from the dark toward the light. As for other painters, I really like Velazquez. And one painter I've always thought is absolutely fascinating is Vermeer; from a technical point of view he blows my mind. I have no idea how he achieved what he achieved. It's so sophisticated. The paintings themselves are beautiful, but if you are in the profession, you can see that technically they are perfect, pure diamonds. And of course I like many other painters. I've made copies of some paintings by Michelangelo, for instance. I also studied Cezanne a lot.

Can you explain to us exactly how you are working? Which are the techniques you are using?

Brushes are my main tool. I use flat brushes with a high quality Japanese black ink, and thin round brushes with white acrylic paint. I work on heavy paper, usually A3 size for comics pages and illustrations. I also use sponge with black ink and old oil brushes with white acrylic for splattering paint, creating “gray” areas, tones between black and white. For color paintings I paint sometimes on large size wood panels, using rollers and acrylic paint. For oil paintings I use “yupo” paper, with traditional oil paint, applying it with brushes, rugs and my hands and fingers. I do not use a pencil, because it has a very thin line. I hardly ever use the line. It outlines forms but doesn't get inside where the volume is.

A few years ago I also started painting digitally, with the Cintiq. It’s a great tool, but when I use it for too many days in a row, I’m missing the tactile feel of the paper, ink and paint, the smell and feel of the material. So I use different tools depending on the project.

What comes first when you are starting a project? Do you start with the drawing?

I am always thinking in images, and often stories or ideas come from an image, or from memory, or something seen at the moment, or a photograph, or a painting….But it's always image, it's visual.

How important are words with your drawings, in your work?

I think the drawings are more important than the words, but there is a balance between them. The drawings definitely take the bigger place, but the words are important; that's why they are there. They do not necessarily follow the drawings. There might be one storyline in the drawings, and then another in the words. That also creates a third space in between the drawings and the words. That's what I find most interesting in this way of storytelling through images and words.

And yet the words are very beautiful, very poetic. You weigh them very carefully.

When I write, I always write and rewrite the same thing many times, and the idea is to try to eliminate any word that is not necessary. That's the method I use, because I do not see myself as a very good writer. So I'm trying to reduce the number of words as much as possible. It's similar to my approach toward images: often things are reduced to black and white, to the necessary. I think somehow through that, also, the words and pictures connect.

The list of comics writers you have worked with is very impressive. Do you choose who you work with? Is your choice based on the theme of the story?

I always picked scripts, if I didn't find the connection with the script it was impossible to work on it. Good writing and a good story is extremely inspiring. One of the greatest treasures, to me, is good dialogue. I admire a good dialogue, and it’s a rare beast, a few writers are good at it. There are many writers I would have liked to work with, although I'm not sure they would've wanted to work with me. I take a lot of freedom. I don’t like scripts that are too meticulous and precise in mise-en-scène descriptions, movements and scenography, I have to have freedom to compose and arrange pages, panels and compositions through my own eyes, and to pick the ways my camera moves. That is one of the most exciting parts of work and I like to have freedom to do my best. If the script is too specific I become blocked and unable to work with it. Working with a writer requires a very different approach than working on my own graphic novel. With someone else's script, the text is beginning while when I work on my own books the beginning is something visual – a certain scene or a series of scenes, like a movie that runs before my eyes and I try to capture the fragments of it. Some graphic novels were born from one single image.

Looking through your bibliography, it seems you do not have an appetite for superheroes. You've drawn a miniseries (6-issue) called Superman: Metropolis written by Chuck Austen which focused on Jimmy Olsen, and 3 issues of Captain America written by Darko Macan. Is this a genre you do not feel comfortable with?

I believe that superficiality, vulgarity, machismo, and ideological conservatism are predominant elements in superhero comics, or at least most of them. Despite all the debates and theories defending the superheroes, they are basically immature common fantasies, and most people like the appeal of those fantasies, the simplicity of a right-versus-wrong world, a world without nuisances and complexity. It might be understandable but it should be called for what it is. The trend is slightly changing now, but it's changing because it became politically correct, fashionable and profitable to appear to be more open, not because inherently superheroes are meant to be multicultural, multi-layered, tolerant or emphatic. Let's stop inventing philosophical discourses about depth and complexity of superheroes – they are meant to be superficial, violent and simple, and putting a different skin color, ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation to them is just a make-up. The interesting stories start with the deconstruction of superheroes, and then you have Watchmen, Dark Knight Returns, or Love and War, but those graphic novels are using the genre's inherent limitations in order to build complex stories upon them. Watchmen is built on the premise that the concept of a superhero is dangerous, potentially catastrophic, and ironically it triggered even more interest in superhero comics. Watchmen etc., are not standard superhero stories – those are exceptions confirming the rule. The reason I worked on Superman and Captain America mini-series was that I expected the same level of deconstruction, but it didn't really happen. I'm not interested in drawing Superman's socks.

French publisher Mosquito has published 14 of your works: Congo Bill (initially published by Vertigo), Invitation à la danse, Rêve de béton, Presque le Paradis, Le rythme du Coeur, King of Necropolis, Rex, La mort dans les yeux, Sexe & Violence, Industriel, Babylone, Tomsk-7, Chaperon Rouge, Les pédés. How did this lasting association come to be?

Mosquito was the first publisher interested in publishing my work in France. And France is still the world's center of the comics, or the kind of comics I appreciate the most, so I was immensely happy to have an entrance to the French audience, and I’m thankful that Michel Jans and Mosquito opened that door. I’m not good at managing and promoting my work, I prefer spending my time creating comics, or doing anything else. So the collaboration lasted, in part, by pure inertia. Also, while living in the USA, I did not follow closely the comics market in Europe, the changes and the evolution of various publishers, I generally don’t follow those things. So when The Starve was published in France by Urban Comics in a very nice edition, and all in one book, it was a beautiful surprise and I didn't know that other French publishers would be interested in such work. (I’m not even sure if Days of Hate were finally published in France, but there was interest? It’s a 300 page book so that might have been a problem.) My last book was published in France by Glenat, Van Gogh, Fragments d'une vie en peinture, in a very lush edition. Unfortunately the book came out in the middle of the Covid epidemic and I was not able to attend the presentation of the book or the exhibition opening at the Gallery Glenat last October. So I have no idea if and with whom I might be able to publish my next graphic novel in France. And it’s ready.

Reading your works, it appears it has a very graphic feeling to it. You have realized numerous silent sequences, and some stories devoid of words. Le Chaperon Rouge remains a favorite, compelling to participate more in the reading, to formulate with words in one's mind, what the eyes are seeing.

I mentioned before the importance of Italian and French movies, and movies in general. Those “silent", wordless graphic novels (Industrial, Babilon, Red Riding Hood) are, in part, homage to silent movies from the beginning of the last century, especially German Expressionism, Russian Avant-Garde movies, as well as Buster Keaton silent movies. There is a special visual quality, the precision of mise-en-scène that is a characteristic of silent movies and got somehow lost with the arrival of sound and spoken word. As if the foundation of storytelling has shifted from the image to the word, and automatically the visual aesthetic lost its purity and quality. The other important work in a similar vein is the work of graphic artists from the beginning of last century (around the same period as the silent movies and the connection is probably not casual). The best known are Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Otto Nückel, but there were others who created wordless illustrated books, which today would be called wordless graphic novels. Such an approach to storytelling has a long tradition and probably spans well over just the western cultural and visual arts tradition. The absence of words brings a different atmosphere and rhythm to pages and it very much changes the way of visual narration. You can even connect it to dance or mime art since those are all narrative forms without words, using body, movement, sound, light, time and space to tell stories. Even if those movies or illustrated stories were created a hundred years ago they are still modern and alive.

What are your favorite work conditions to create? Studio space, music, time of the day…? Do you begin your working day with a fixed number of pages to create?I work in my studio, I don’t need a big space, except if I work on some large-size painting projects or animations. I work at night, and also in the early morning hours when possible, it depends how I can organize my day, And it doesn't always depend on me, there are other people in my life. Sometimes I listen to music while working, as a background, for days, sometimes I prefer silence. I guess rules change depending on the circumstances and projects. I lived in many different places, cities, houses and rooms, so I learned to adapt.

Do you work alone, or is there a muse who inspires you, a mentor you look up to? Who are your artistic influences, or what movement?

n comics, I always work alone, I don’t see any other way of doing it. I heard of artists who have assistants but I wouldn't know how that works. Creative work is done in solitude, and even if it's a collaborative project, the creative parts are conceived and prepared in solitude. When, for example, I work on Live Painting + Live Music performances, or animation projects, I work with other people, but everybody brings hers or his piece of creativity to the table. I enjoy working with other creative people, it opens up the space and possibilities, there is always something to learn and exchange, and you never know where and when some working experience will reappear in another project.

Do you execute one page at a time from start to finish? Or do you work on several pages at a time, going back once the ink has dried to add effects afterwards?

I used to always work on the page until it's finished before starting the next one, but for the past years I often work on several pages simultaneously. The initial stage of work on the page is always the most exciting and creative, as you enter later stages the work is more and more mechanical.

Looking at your panels, at your page the eye is directed by the shadows. How do you construct your compositions to manage this effect?

Composition of the page and panels is one of my favorite parts. I usually sketch it on a separate paper, very roughly, just to get the idea of the main black and white areas, the balance and composition, then I apply it to the real page. You can get lots of energy and tension just from the composition of the panel and the page, it has a powerful narrative drive.

Your work relies heavily on visuals. How do you approach translating space and time in images?

I think in images more than words, I believe that comics are a combination of images and words, but for me, the image always comes first. There is an element of time and rhythm in the comics, there is a third space in between panels and pages, between images and words, and that third “invisible” space is one of the most exciting elements of narration in comics. It’s difficult to control it and achieve it. I love it when it works and when it's used well, like in some graphic novels by Alan Moore, Cyril Pedrosa or Larcenet.

Do you work with thumbnails for each page? With pencils for each panel, before going to ink and paint?

I use pencils very scarcely, in a minimalistic, sketchy way, almost unreadable to anyone but me. My drawings are not based on lines, but on shapes, so it's pointless to create precise preparatory pencil work because it’s simply useless when big blocks of black and white are applied over it. So most of the work is created directly in ink.

How do you create your characters? Do you work with a sketchbook to refine them visually? Do you see them as a projection of yourself?

I hear them. I hear their voices and I see their faces and bodies. There is always lots of sketching, trying different angles and moods. No, I don’t want them to be like me, although, probably, unconsciously, there is a projection of myself in all of them. You can't escape from yourself, but it's good to try to.Regarding Van Gogh

Common sense would say that an homage to Vincent van Gogh must be color. Why did you choose Black & White?

I would say black and white chose me:)

Actually, the early paintings of Van Gogh are predominantly monochromatic, his heroes were Jean-François Millet and Rembrandt, painters of a limited palette, and only later he finally opened up towards the richness and brightness of colors. It is pointless to try to reproduce Van Gogh’s colors without making them banal, and I never intended to. However, the light and shadow, the extremes of black and white are appropriate ways to describe a life stretched to emotional and physical extremes, a life completely absorbed with obsessions, a desperate desire to belong, and a serious mental illness. It's not a traditional biography, although it is based on facts and it follows the chronology and authentic locations. It portrays the emotional states rather than events. Each of 15 episodes in the book takes place in a documented location at a specific time, but those events are invented, they are constructions of something that might have happened or might have not - as if we are invisible witnesses of silent moments in Vincent's life. The episodes are wordless, and the letter at the end of it, which corresponds to the place and time of the episode, is like a post scriptum, a comment which is sometimes in harmony and sometimes in disparity with the episode.

You have mentioned that you read a lot.

I like to read. I do not have a TV or anything.

Do you have any favorite writers?

I have a lot. Whatever I'm reading at the moment. Right now, I'm reading essays by Joseph Brodsky. I like his poetry, too. Octavio Paz is very important for me. Anything by him interests me. Of course, there are things that you can always come back to-like Dostoevsky-you read it again, and it's like reading it for the first time. If you still have time and patience for it. I like Pier Paolo Pasolini a lot as a writer-for me, he is primarily a writer. I really think that his poetry is the most fascinating part of his whole body of work. His movies are great, but for me the poetry was a big discovery. It's a combination of everyday and trivial with ancient and eternal. The ability to discover classical beauty in the most ordinary dirty street dog in Naples. Another favorite writer of mine is Bohumil Hrabal. And also Stanislav Habjan. But you can read him only in Croatian.

What about films?

When I was a kid, Zagreb had a great theater, the Kinoteka. They used to show movies by different directors, and many works from the past. I saw German Expressionist movies from the 1920s and Russian avant-garde films. We were able to see all kinds of things, like old films by Bunuel, Buster Keaton, almost all of Fassbinder's films, Herzog's films. So I grew up seeing a lot of good stuff. In film storytelling and narration, I think there are a lot of similarities to graphic novels.

Danijel is represented by IllustrationZone:

https://www.instagram.com/danijelzezelj/

https://www.illustrationzone.com/danijel-zezelj

https://www.instagram.com/illustration.zone/

Interview and story by Bruce Lit http://www.brucetringale.com/